Functional Nutrition and ADHD: Supporting the Foundations of Attention and Regulation

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a highly heritable neurodevelopmental condition, with genetic factors accounting for an estimated 77–88% of risk. Variants affecting dopamine and norepinephrine signaling, synaptic plasticity, and cortical network development shape how the brain processes attention, impulse control, and executive function from early life onward. (1)

Acknowledging this genetic foundation that underlies most cases of ADHD is essential. ADHD is not caused by parenting style or lifestyle, and it is not something that can be “fixed” through nutrition alone. At the same time, genetic predisposition does not operate in isolation. Gene expression, symptom severity, and functional outcomes are strongly influenced by environmental factors, including nutrition, detoxification, metabolic health, sleep, stress, and immune signaling. The goal for nutrition and lifestyle interventions in ADHD is not to override genetics, but to optimize cognitive function by ensuring the brain has the nutrients required to function effectively and to remove barriers like poor sleep, food sensitivities, and gut microbiome imbalances.

Genetics Set the Blueprint; Physiology Shapes Expression

Genes involved in the transport and function of neurotransmitters influence how efficiently the prefrontal cortex sustains attention and modulates behavior. However, these same pathways are also highly dependent on certain nutrients.

ADHD can be understood as a condition in which:

Neurotransmitter systems require higher micronutrient support

Energy metabolism in the brain may be less efficient

Stress and inflammatory signaling more readily disrupt executive function

Sleep and circadian misalignment have amplified cognitive effects

This helps explain why individuals with similar genetic risk profiles can present with markedly different symptom burdens, and why diet and lifestyle can have a positive impact.

The Gut–Brain–Immune Axis

Genetic vulnerability in ADHD may increase sensitivity to immune activation and inflammation. Research suggests that alterations in gut microbiota composition and intestinal barrier function can affect how the brain and immune system communicate, influencing mood, focus, and nervous system regulation. (2)

ADHD is associated with differences in gut bacteria in some people. Studies comparing children with ADHD to those without have found that people with ADHD often have reduced microbial diversity and reduced abundance of certain bacterial species like Bifidobacterium.

Certain gut microbes produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which help support the gut lining, regulate immune activity, and send signals to the brain through the gut–brain axis. Research has found that children with ADHD often have lower levels of specific SCFAs like butyrate.

The gut lining plays a role in immune and brain signaling. Changes in gut barrier integrity can influence how immune signals travel through the body, potentially affecting mood, focus, and stress sensitivity.

Medication, diet, sleep, and stress all affect the microbiome. ADHD medications, eating patterns, sleep quality, and stress levels can all change gut bacteria, which is why researchers are careful when interpreting microbiome findings.

Some clinical trials have found improvements in certain cognitive measures or quality of life with specific probiotic strains.

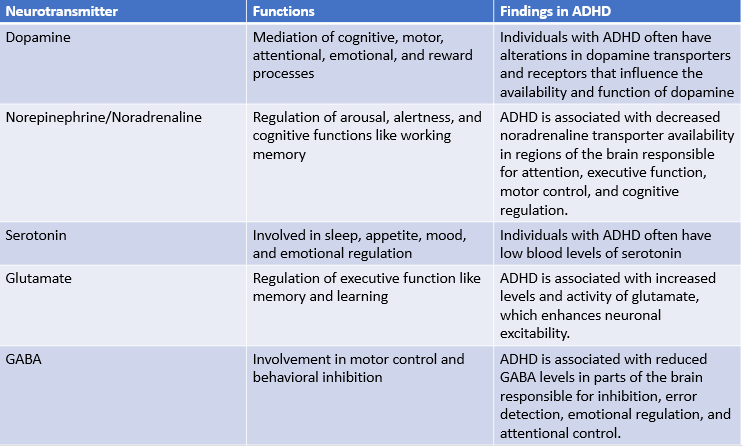

Neurotransmitters and the ADHD Brain

Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers that support communication between brain cells. Dopamine and norepinephrine play central roles in focus, motivation, and emotional regulation, and in ADHD their signaling tends to be less consistent in brain regions involved in attention and self-control. (3)

Dopamine helps the brain decide what is important and worth paying attention to. When dopamine signaling is less consistent, the brain may struggle to stay engaged with tasks that feel boring, effortful, or not immediately rewarding. This can look like distractibility, difficulty starting tasks, or needing constant stimulation to stay focused.

Norepinephrine helps regulate alertness and attention. When this system is out of balance, it can be harder to stay mentally “on” without becoming either overstimulated or mentally fatigued, especially during schoolwork or long periods of concentration.

These brain messengers rely on the body’s overall health. Sleep, stress, nutrition, blood sugar balance, and inflammation can all affect how well neurotransmitters work. That’s why ADHD symptoms can change from day to day and why supporting the body with diet and lifestyle can make a meaningful difference in how the brain functions.

Nutrient Demands in a Dopamine-Dependent Brain

Neurotransmitter signaling relies on adequate availability of specific nutrients. (4)

Iron and zinc, which are required for dopamine synthesis and receptor function

Omega-3 fatty acids, which support neuronal membrane integrity and synaptic signaling

Magnesium, which modulates neuronal excitability and stress responsivity

B vitamins and carnitine, essential for methylation, neurotransmitter synthesis, and mitochondrial energy production

In individuals with ADHD, suboptimal status of these nutrients may not create the condition, but can magnify cognitive symptoms.

Blood Sugar Regulation and Executive Function

Brains affected by ADHD often show heightened sensitivity to metabolic stress. Rapid fluctuations in blood glucose can impair attention, emotional regulation, and working memory, particularly in children.

Stabilizing blood sugar through balanced meals can reduce avoidable cognitive volatility, allowing behavioral, educational, and pharmacologic interventions to work more effectively.

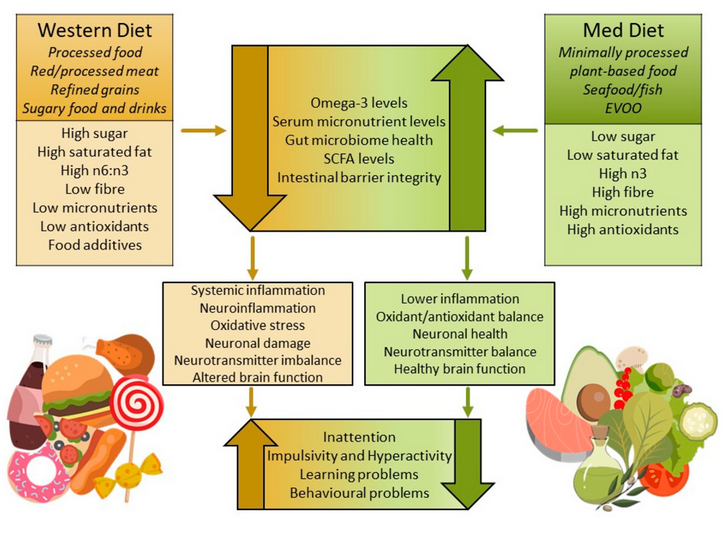

Diet Quality and Cognitive Function

Research shows that the foods we eat can influence how well the brain works, including learning, memory, and thinking skills. Diets high in saturated fats and added sugars, which are common in many Western eating patterns, have been linked to poorer performance on memory and learning tasks and to changes in the structure and communication between brain cells that support neuroplasticity, or the brain’s ability to adapt and form new connections. By contrast, diets richer in whole, nutrient-dense foods such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats are consistently associated with better cognitive function and stronger support for the chemical and cellular processes involved in learning and memory. These effects are thought to occur in part because nutrient-rich diets help maintain synaptic integrity, support antioxidant defenses, and promote balanced signaling in pathways that are important for attention and cognitive flexibility. (5)

Image source: https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15050335

Food Sensitivities and ADHD

Recent research suggests that food sensitivities and intolerances may play a role in ADHD for a subset of individuals. In one study, over 80%participants with ADHD showed high reactivity to common foods such as cow’s milk, other dairy products, and wheat or gluten when tested for food intolerances, and these reactions were found alongside relationships between certain nutrients and ADHD symptom severity. (6) This research highlights that individual differences in how the body responds to specific foods may be linked to behavioral and cognitive symptoms in some children and adults with ADHD. Exploring these patterns through careful monitoring or elimination and re-challenge (under professional guidance) may help some families identify foods that worsen symptoms and support a more personalized approach to diet and behavior management.

What About Medication?

Pharmacologic treatment remains an important and evidence-based option for many individuals with ADHD. Stimulant and non-stimulant medications can meaningfully improve attention, impulse control, and academic or occupational functioning, and for some individuals they are essential for daily stability and safety. From an integrative perspective, medication often works best when considered alongside foundational supports like sleep, nutrition, exercise, and cognitive training, that influence how the brain responds to treatment.

However, research shows that diet and lifestyle can meaningfully influence both ADHD symptom burden and medication responsiveness. Research and clinical observation suggest that addressing food allergies and sensitivities, micronutrient insufficiencies, blood sugar dysregulation, sleep disruption, and inflammatory or metabolic stressors may, in some cases, reduce symptom severity or improve medication tolerability. In these contexts, nutritional interventions could be explored before a trial of medication, and in those already on medication, optimizing nutrition may further improve symptoms.

Cognitive Training as a Complementary Support: Evidence from LearningRx Research

In addition to nutritional and lifestyle foundations, targeted cognitive training interventions can support domains of executive function that are often affected in individuals with ADHD. One example is clinician-delivered, one-on-one cognitive training, offered by LearningRx, which has been evaluated in multiple peer-reviewed studies. Research involving children who completed structured cognitive training programs demonstrated statistically significant improvements in key cognitive skills like working memory, long-term memory, logic and reasoning, and processing speed, when compared with control groups, along with qualitative gains in confidence and task-persistence reported by caregivers. A large study of their ReadingRx cognitive training intervention also found medium to large effect size improvements across multiple cognitive measures, including attention and working memory, with similar benefits observed regardless of ADHD status.

These gains reflect experience-dependent neuroplasticity, a process that is energetically and nutritionally demanding. Adequate availability of micronutrients involved in neurotransmitter synthesis, mitochondrial energy production, myelination, and synaptic remodeling, like iron, zinc, omega-3 fatty acids, magnesium, carnitine, and B vitamins, have the potential to enhance an individual’s capacity to respond to intensive cognitive training.

Read more about LearningRx’s peer-reviewed research here.

An Integrative Model of ADHD

ADHD is influenced by both genetic and physiological factors, and effective support often involves multiple strategies. Often used alongside conventional treatments, nutrition and lifestyle interventions can help optimize brain function by supporting energy metabolism, neurotransmitter balance, and stress regulation.

© 2026 Ellie Whitenack, MS, Integrative Nutrition, LLC. All rights reserved.

This content is for educational purposes only and is not intended to diagnose, treat, or replace medical care.

Grimm O, Kranz TM, Reif A. Genetics of ADHD: What Should the Clinician Know?. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(4):18. Published 2020 Feb 27. doi:10.1007/s11920-020-1141-x

Han D, Zhang Y, Liu W, et al. Disruption of gut microbiome and metabolome in treatment-naïve children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. BMC Microbiol. 2025;25(1):381. Published 2025 Jul 2. doi:10.1186/s12866-025-04048-7

da Silva BS, Grevet EH, Silva LCF, Ramos JKN, Rovaris DL, Bau CHD. An overview on neurobiology and therapeutics of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Discov Ment Health. 2023;3(1):2. Published 2023 Jan 5. doi:10.1007/s44192-022-00030-1

Gibson GE, Blass JP. Nutrition and Functional Neurochemistry. In: Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW, et al., editors. Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. 6th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK28242/

Pinto S, Correia-de-Sá T, Sampaio-Maia B, Vasconcelos C, Moreira P, Ferreira-Gomes J. Eating Patterns and Dietary Interventions in ADHD: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2022;14(20):4332. Published 2022 Oct 16. doi:10.3390/nu14204332

Hunter C, Smith C, Davies E, Dyall SC, Gow RV. A closer look at the role of nutrition in children and adults with ADHD and neurodivergence. Front Nutr. 2025;12:1586925. Published 2025 Jul 30. doi:10.3389/fnut.2025.1586925