Long COVID: A Systems-Based, Integrative Perspective on Recovery

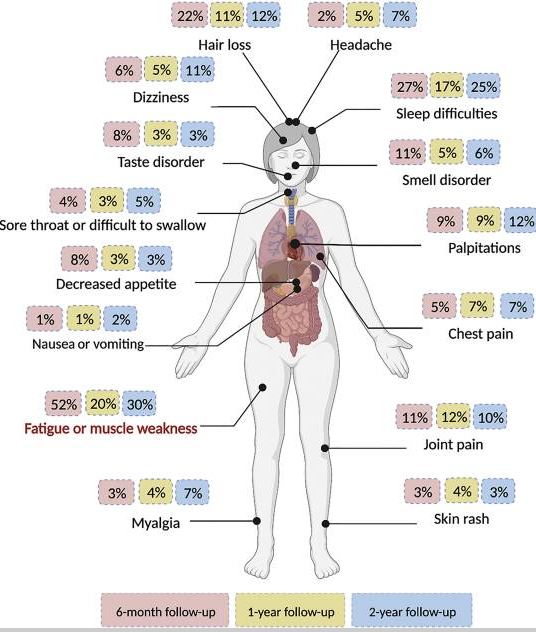

Long COVID is increasingly recognized in research and clinical practice but effective treatments have been slow to emerge. Individuals may experience persistent fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, dysautonomia, sleep disturbance, mood changes, gastrointestinal symptoms, and post-exertional malaise for months or even years following acute infection. Importantly, these symptoms can occur even after mild or asymptomatic initial illness.

From an integrative nutrition perspective, Long COVID is best understood as a state of prolonged physiological dysregulation, a maladaptive set of responses involving overlapping disturbances in immune signaling, metabolic capacity, nervous system regulation, and inflammatory control. This is a familiar paradigm in the functional medicine world, bearing marked similarities to conditions like chronic Lyme, Mast Cell Activation, and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS).

Image source: PMID: 39171285

Multiple Pathways, Many Presentations

One of the defining features of Long COVID is its variability. Few presentations are identical, and symptom patterns often fluctuate over time. This heterogeneity suggests that Long COVID is not driven by a single mechanism, but rather by a convergence of interrelated processes that differ by individual.

Current areas of investigation include:

Persistent immune activation or immune maladaptation

Altered neuroimmune signaling and neuroinflammation

Autonomic nervous system dysfunction

Impaired mitochondrial and metabolic resilience

Endothelial and microvascular dysfunction

Hypercoagulation of infectious and genetic origin

Changes in the gut microbiome and intestinal barrier integrity

Reactivation of latent infections in susceptible individuals

The Immune System: Sustained Activation

A recurring observation in both research and clinical practice is that Long COVID reflects an immune system that remains activated but poorly regulated. Rather than returning to a balanced baseline after infection, immune signaling may remain activated, inefficient, or misdirected. (1)

This has several downstream consequences:

Sustained low-grade inflammation

Increased energy demand

Heightened sensitivity to stressors

Exaggerated symptom flares with exertion, illness, or sleep disruption

Importantly, immune function is energetically expensive. When immune activity remains elevated, it places ongoing strain on mitochondrial function and nutrient reserves. Nutritional strategies in this context are not intended to “boost” immunity, but to support immune regulation, tolerance, and resolution, while ensuring adequate substrates for energy production and repair.

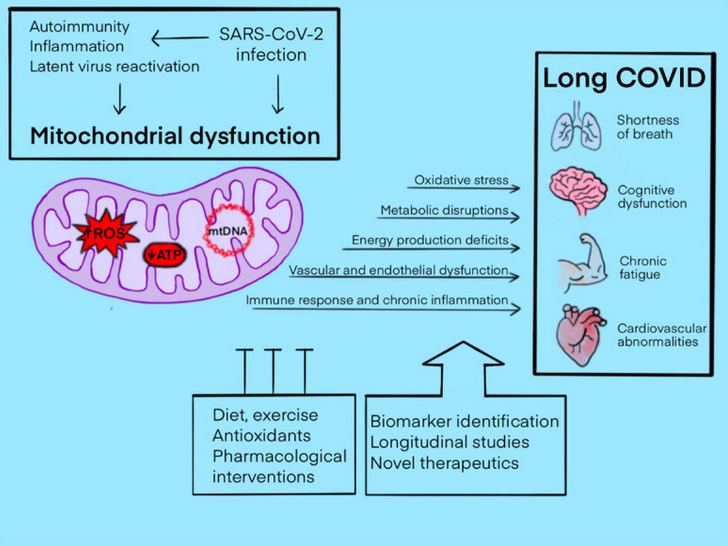

Mitochondrial and Metabolic Vulnerability

Many Long COVID symptoms like fatigue, exercise intolerance, cognitive slowing, and post-exertional malaise, point toward impaired mitochondrial function, meaning the body has difficulty producing and regulating energy in response to everyday demands. Research demonstrates that SARS-CoV-2 infection can disrupt mitochondrial function, leaving cells less efficient at generating energy and more prone to oxidative stress, while simultaneously increasing the need for energy-intensive repair. (2)

Mitochondria are not only responsible for energy production, but also play a critical role in immune signaling, redox balance (the balance between oxidative stress and antioxidants that counter it), and cellular recovery. When mitochondrial function is impaired, oxidative stress tends to rise, the energy demands of ongoing immune activation become harder to meet, and recovery from exertion is delayed. This helps explain why many individuals with Long COVID experience fatigue and post-exertional malaise, where physical, cognitive, or emotional effort leads to symptom worsening. In other words, when mitochondria are damaged and have reduced capacity to generate energy, and the immune system is activated and using a tremendous amount of energy to sustain its maladaptive response, there is often little energy left over for daily tasks.

In practical terms, this means:

Normal daily activities may exceed available energy

Stressors that were once tolerated now provoke setbacks

Recovery requires careful pacing and intentional resource rebuilding

From a functional nutrition perspective, the goal is to reduce unnecessary metabolic stress while supporting mitochondrial resilience and repair. This includes stabilizing blood sugar to prevent energy crashes, ensuring adequate intake of micronutrients involved in mitochondrial enzyme function, like B vitamins, magnesium, and iron, and supporting antioxidant capacity through nutrients like vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium, which help manage oxidative stress generated during energy production. Adequate protein intake is also essential, as amino acids provide the structural and signaling components needed for cellular repair and immune regulation. Nutrients like coenzyme Q10 and omega-3 fatty acids have been studied for their roles in mitochondrial efficiency and inflammation modulation, and may offer supportive benefits in some individuals. Rather than pushing the system to perform, targeted nutrition aims to create the conditions in which energy production, immune regulation, and recovery can gradually normalize.

Image source: PMID: 38668888

Hypercoagulation and Biofilms

In some cases of Long COVID, the body’s fibrin production and clot-regulating systems can become out of balance, leading to a state known as hypercoagulation, in which more of the protein fibrin is produced than the body can efficiently break down. Fibrin plays an important role in normal wound healing, but when excess fibrin accumulates, it can contribute to the formation of sticky networks known as biofilms. These structures can trap microbes, viral fragments, and cellular debris, making them harder for the immune system to fully clear. As a result, the immune system may continue responding as though a threat is still present, prolonging inflammation and symptoms. Genetic predispositions, chronic inflammation, or prior infections may increase fibrin production, and when fibrin breakdown is impaired, microvascular circulation and tissue recovery can suffer. his framework helps explain why some people with Long COVID experience persistent fatigue, heaviness, or vascular-type symptoms even when standard clotting tests appear normal, because the issue may involve subtle imbalances in how fibrin and biofilms are regulated within tissues rather than large, detectable clots, potentially contributing to ongoing inflammation and the persistence of viral remnants. (3)

Long COVID and Spike Protein

Another aspect of Long COVID being explored by researchers is the impact of the virus’ spike protein. The spike protein is a structure the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to attach to and enter human cells. During an active infection, the virus enters cells and uses the cell’s own machinery to produce viral components, including spike protein, as part of making new virus particles. Some researchers have proposed that in a subset of individuals, viral genetic material or viral remnants may persist in certain tissues, leading some cells to continue producing or releasing spike protein fragments even after the acute infection has resolved. (4) If this occurs, the ongoing presence of spike protein may continue to stimulate the immune system, contributing to chronic inflammation rather than allowing the body to fully return to baseline. Spike protein has been shown to interact with blood vessels, immune cells, and the nervous system, which may help explain symptoms such as fatigue, brain fog, circulation issues, or autonomic dysfunction in some people with Long COVID.

The Nervous System and Autonomic Regulation

Autonomic dysfunction is increasingly recognized in Long COVID, with symptoms such as dizziness, palpitations, temperature dysregulation, gastrointestinal motility issues, and heightened stress sensitivity. These patterns suggest disruption in communication between the brain, immune system, and peripheral tissues and reinforce the importance of nervous system support as a therapeutic target.

Nutrition and lifestyle interventions such as regular meal timing, adequate protein intake, micronutrient repletion, sleep optimization, and gentle regulation of circadian rhythm serve as stabilizing inputs to the nervous system, helping reduce physiological threat signals and support autonomic balance. Neural retraining and other nervous system–stabilizing practices aim to reduce persistent threat signaling in the brain and autonomic nervous system, supporting greater physiological safety and flexibility so that immune regulation, energy production, and recovery processes can normalize over time.

The Gut–Immune Connection

The gastrointestinal tract represents one of the most significant interfaces between the immune system and the external environment. Alterations in gut microbial composition and intestinal barrier function have been observed following SARS-CoV-2 infection, and these changes may influence systemic inflammation and immune signaling. Supporting digestive function, microbial diversity, and barrier integrity can therefore reduce inflammatory burden and improve nutrient assimilation—both of which are critical in prolonged recovery states.

Environmental, Lifestyle, and Cumulative Stress Load

Long COVID does not occur in isolation. Pre-existing stressors like nutritional deficiencies, chronic sleep disruption, environmental exposures, psychological stress, or prior illness, may reduce physiological reserve and prolong recovery.

Along with genetics, a cumulative load model helps explain why some individuals recover quickly, while others struggle for months. From this perspective, addressing Long COVID involves lightening the total burden on the system, not just targeting one pathway.

This includes:

Prioritizing restorative sleep

Reducing inflammatory dietary inputs

Optimizing nutrient levels

Supporting hydration and electrolyte balance

Managing physical and cognitive exertion

Addressing psychosocial stressors

An Integrative Approach to Recovery

Long COVID does not follow a single standardized treatment pathway, and effective care requires individualized assessment and ongoing adjustment. While conventional treatment options remain limited for many patients, functional nutrition can support recovery by addressing modifiable root contributors to ongoing symptoms, including immune imbalance, mitochondrial dysfunction, and nervous system dysregulation. When these drivers are systematically addressed, meaningful improvement and recovery is possible.

© 2026 Ellie Whitenack, MS, Integrative Nutrition, LLC. All rights reserved.

This content is for educational purposes only and is not intended to diagnose, treat, or replace medical care.

Liu Y, Gu X, Li H, Zhang H, Xu J. Mechanisms of long COVID: An updated review. Chin Med J Pulm Crit Care Med. 2023;1(4):231-240. Published 2023 Dec 6. doi:10.1016/j.pccm.2023.10.003

Molnar T, Lehoczki A, Fekete M, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in long COVID: mechanisms, consequences, and potential therapeutic approaches. Geroscience. 2024;46(5):5267-5286. doi:10.1007/s11357-024-01165-5

He D, Fu C, Ning M, Hu X, Li S, Chen Y. Biofilms possibly harbor occult SARS-CoV-2 may explain lung cavity, re-positive and long-term positive results. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:971933. Published 2022 Sep 28. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2022.971933

de Melo BP, da Silva JAM, Rodrigues MA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and Long COVID-Part 1: Impact of Spike Protein in Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Long COVID Syndrome. Viruses. 2025;17(5):617. Published 2025 Apr 25. doi:10.3390/v17050617